I’ve been using Zwift pretty extensively for the last few months. For anyone unfamiliar: Zwift is a VR Biking platform. That means, you can put your bike on a smarttrainer, connect it to your pc (directly via ant+ / ble or by bridging with your phone), and then you can ride virtual worlds without having to go outside. Sounds not too bad, right?

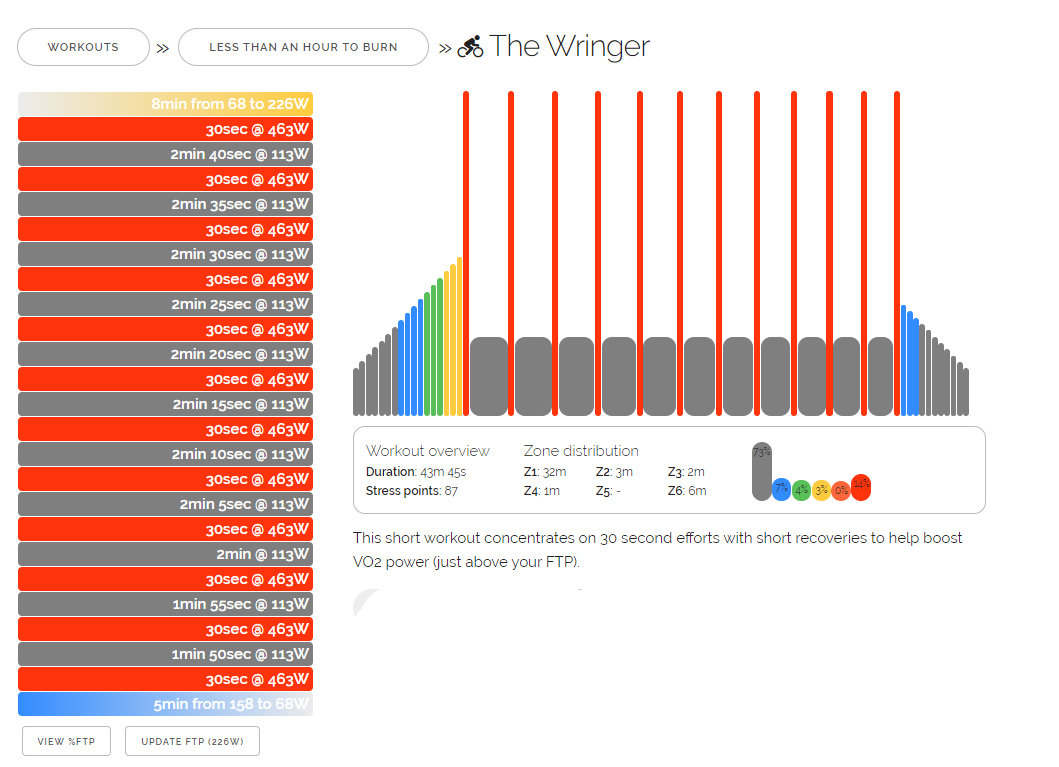

After a few sessions, just riding became kind of tedious, so I’ve tried to do some of the preconfigured workouts. You can either do workouts by themselves or follow a trainingplan, which consists of multiple workouts that you have to complete to a given date. The workouts all have the same structure. They consist of different blocks, that can have a variety of requirements. The blocks that are available are either steady pedaling, ramps (up or down) or intervals (alternating steady blocks of high and low power which are repeated to a predetermined extent). Basically, there are some more types, but we’ll get back to that later. Let’s take a look at one of these workouts for example.

My main resource for zwift workouts is WhatsOnZwift. You can view the built-in plans and workouts there and also browse custom workouts. You can download and import the custom workouts also, but sadly, you can’t download the built-in ones. Sadly because I’d like to use the original files for some reverse-engineering. But let’s go with what’s available. The following example is a custom workout I created myself, but you can just download any of the custom workouts from WhatsOnZwift to play around with. After downloading the workout, you’ll get a .zwo-file, which can be opened with an editor of your choice. And, as expected, the file is just plain xml:

| |

As you can see, the file itself consists of two parts: A step-by-step description of the workout itself, and some additional metadata. The metadata contains information like the author of the workout, along with its name and description. Since Zwift currently supports both biking and treadmill running, there’s an additional element specifying the type of sport the workout is targeting. You can also add tags to the workout for increased searchability.

Now let’s jump into the more interesting part. The workout consists of a Warmup, which is basically a ramp from 25% to 75% of your FTP. Note that all performance values are based on a percentage of your individual FTP. This warmup takes 300 seconds, so 5 minutes. The warm-up is followed by two interval sessions, which are interrupted by a short 3-minute break to get your heartrate back down. Each of the interval session consist of 10 repeats of 30 seconds at 130%, followed by 30 seconds at 50% FTP. After completing both sessions, there’s an additional 3 minutes of easy pedaling at 50% before beginning the cooldown. The cooldown again as a reverse-ramp, lowering the power from 75% to 50% over a period of 8 minutes.

So, nothing too complicated, right? I’ve been checking out some workouts and noticed that there’s a bit more variety to take care of. However, zwift doesn’t seem to publish any kind of developers guide to check out the details. On the other hand, I found this unofficial guide on GitHub. So, as long as it works, I’ll stick to that.

The first big chuck of information I’m interested in are the different types of workouts and how they are different from each other. There are additional types such as FreeRide, MaxEffort or Ramp (which looks very similar to a warmup) and each of those uses different parameters to describe the session. For example, freerides don’t offer a way to set a power output, which makes total sense.

All of the workouts can contain sub-elements called textevent. If you’ve been doing some of the beginner plans on zwift, you might have seen those. They basically show up in the middle of the workout, printing some text on the screen which is usually either motivational gibberish or information on what to focus on during the workout. They are defined by adding a text and a duration on how long the text should be visible. To define the time the text will appear, I’ve only seen timed offsets so far. However, the guide says there’s also an option to specify the time based on distance.

I could dive in the guides details probably forever, but for now, let’s just try to build an app that can read and write the workout I’ve added above. With a basic implementation, more workout types and parameters can then be added more easily.

So, to start we need to create a data structure that matches the given xml. Don’t worry too much about the naming here because the matching will be done with attributes later. Also, it’s a good practice to be more consistent in the naming than Zwift. I came up with the following classes:

| |

That’s it for now. With this state, I can now describe the workout from the xml file, but the automatic mapping is not working just yet. Let’s now add the attributes for the name matching. Note that I added an enumeration for the sportsType-property. This doesn’t need any additional handling tough, the (de-)serialization automatically picks the matching string representation.

| |

Note that I used different attributes for different purposes. Each class is decorated with an XmlRoot-attribute, while each property uses an XmlElement-attribute. At least for the WorkoutFile-class. That’s the default behaviour, but it doesn’t work for the workouts themselves. If I would use XmlElements for these too, I’d end up with sub-nodes for these too.

That’s how a workout would look like with XmlElements as Items:

| |

But since this is what we want, we’ll have to use XmlAttributes instead:

| |

The xml matching is almost working at this point. The last step now is to define the collection properties. Zwift uses Tags for each concrete workout type, so we can’t go with something like

| |

To achieve this, all I need to do is adjust both collections as follows:

| |

And that’s basically it! To test the functionality, I created a new console application and added methods to both read and write a workout file. Let’s focus on reading for now:

| |

Note that you need to specify the types that the object will be serialized to. This includes nested types, so I set WorkoutFile as first argument and an array including all of the workout types and Tag as the second one. When running the application now, the file gets deserialized and I get an object representing the workout. Seems to work well so far!

Now, to the deserialization part. This worked out to be a bit trickier than the deserialization, because there’s a lot of metadata automatically being added to the xml file. However, since I don’t have control over the schema, I’ll have to get rid of all that. Here’s how I achieved that: First I recreated the workout by code, so I’d be able to compare both files side-by-side.

| |

To serialize this, I added the following method to my program. As I mentioned, I had to remove the xml metadata from the output file, so I added some custom XmlWriterSettings. Additionally, I’ve added an empty string to the XmlSerializerNameSpaces-Array to prevent the serializer from adding namespaces to my xml elements.

| |

And with this setup, I got the following result:

| |

Seems fine, so far. Of course I don’t have any options included yet, but the base is working and can be easily extended. Also, the next step could be to integrate some kind of GUI to create and edit custom workouts, so stay tuned for that!