As a software developer, you’ve probably heard about Docker and perhaps already used it. But if you’re like me, you’ve been observing the topic from a distance with some interest, but you haven’t gotten into it yet.

In this article I would like to introduce you to the concept of docker and the “big picture”. This post will not be a detailed tutorial, but will give you an overview of the technology and help you get started.

Docker is software for isolating applications through container virtualization. Before we start with Docker as a practical example, I would therefore like to discuss containers in general and describe what distinguishes them from virtual machines.

What are containers?

Imagine a company wants to put a new application into operation. In the past, this was usually done in such a way that new hardware was purchased for this purpose; each physical server was responsible for one application. When a new application was added, however, it was often unclear how much power would be required for the new application, which is why it was often overdimensioned. This, of course, also results in unnecessary costs.

The successor of this concept, which is often used today, are virtual machines. Physical hardware is distributed across multiple virtual machines on which the applications run. This means that an application is no longer managed per physical server, but per VM.

However, this concept is already problematic: Although the number of servers is reduced, each VM still requires its own OS installation, which in turn requires license fees (at least in most cases), as well as time for administration of the operating system, etc. This of course was also the case with the previous concept, but we’d like to circumvent that.

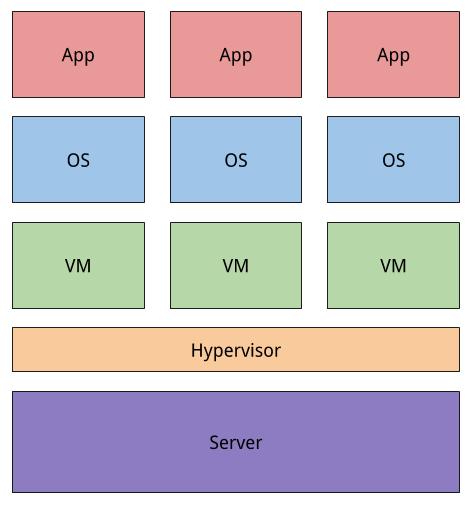

In addition, every operating system needs a whole bunch of storage space, which could otherwise be used elsewhere. This is best illustrated in the following graphic:

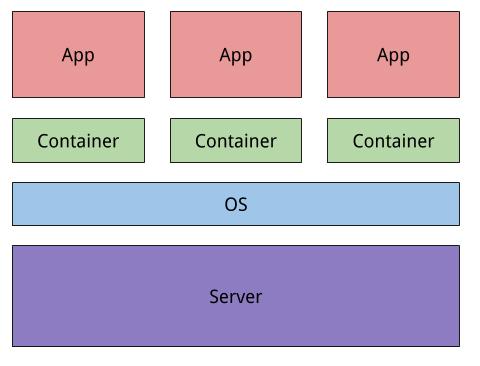

The graphic shows a classic hypervisor architecture with three virtual machines. Okay, basically the points OS and VM belong together, but to compare the graphics better with the container counterpart, I have listed them separately here. In return, let’s look at the structure of a container-based architecture:

As you can see, the layer of hypervisor and VMs disappeared. The containers in which the applications run share the operating system. This approach is much lighter, since no entire OS needs to be loaded to start a container. When you try Docker, you will notice that a Docker container usually takes less than a second to launch. In addition, much less storage space is generally required, as the various operating systems are no longer required.

The fundamental difference between hypervisor and container technology is therefore the common operating system basis of container-based architecture. Next, let’s look at Docker as a concrete example.

What is Docker?

First of all: Docker is neither the first nor the only container technology. Docker has become the de facto standard thanks to its ease of use and other features and is used productively by a large number of organizations worldwide. One of these important feature of Docker is Docker Hub, which I will cover soon. The many additional applications and plugins are not only provided by Docker Inc., but also by 3rd party developers and companies.

The company behind Docker, Docker Inc. was founded in San Francisco in 2010 under the name dotCloud and was renamed in 2013.

Docker Inc. is not the same as Docker. The software itself is open source and released under the Apache 2.0 license. At the core of Docker is the Docker engine, which is used to create and run images. You can think of an image like a disabled container or a template for one.

Docker Hub is a platform (a so-called image registry) on which images can be exchanged. For example, if you want to create a PHP application and your container needs an Apache web server and a PHP installation, you can search for pre-built images on Docker Hub and integrate them into your project. You will find a multitude of offers for various applications there, which means that you hardly have any effort in creating your own images. You can think of Docker Hub as a “PlayStore for enterprise applications”.

DockerHub is not the only image registry. Besides this, there are many other cloudbased registries, but there are also ways to host one in your own network. This is especially useful for business applications with a no-cloud policy (however, you can also mark your Docker Hub images as private so that only you have access to them).

For what kind of software can Docker be used?

Containers can be used for both stateless and stateful applications. Although many advantages of containers only become visible with stateless applications, there are a large number of images for database management systems, for example. Containers will keep your data when turned off, so you can easily run a PostgreSQL instance with Docker, for example. So-called “volumes” can also be used to hold this data even if a container is destroyed.

Container Orchestration

A buzzword you’re sure to stumble upon early on is container orchestration. But what’s it all about? It refers to the (automated) cooperation of many individual services within a complex application. Docker has its own tool for this: Docker Swarm allows you to orchestrate containers across multiple hosts, so you can manage containers across Microsoft Azure or Amazon AWS, for example. Of course, there are also alternatives in this area, for example Kubernetes, initiated by Google.

Wrap-Up

Docker offers developers a way to run applications in isolation without having to use a VM for each app. Additional tools such as the Docker Hub enable the exchange of images and thus speed up the creation of your own images.

I am aware that this short introduction can only give you a minimal insight into how containers work. I hope, however, that I have awakened your interest in getting more involved with this topic and that you now know what to look for. After all, the same applies here: If you want to learn the subject as a developer, you’re best served by getting your hands dirty.

You can download Dockerhere, for which you need a free Docker ID (this is also valid for DockerHub). If you want to learn more about the topic, you can find several guides online, I recommend to have a look around at Medium.com, Pluralsight or YouTube.