This post represents an overview of version control with git. The mentioned commands and parameters are only a small part of what’s possible. Git is a popular system for version control. Projects on git are called Repositories. Repositories can be used local or with a server. There are several free hosters, for example:

Installation

- Linux (Debian-based)

| |

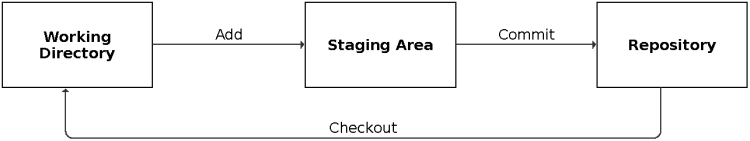

Elements

Git-Repositories are separated into working directory, staging area and repository. The working directory is the local copy of the repository.

Changes on the files are saved here. The repository is the shared project of all contributing persons. Using the staging area, a developert can decide, which elements he/she wants to save from the working directory to the staging area.

Basic administration of a repository

All commands are initiated with the keyword git.

Initialization of a folder as repository:

| |

Editing / creating files: test.txt

| |

Each commit is commented with the -m-flag.

This gives the developers a fast overview about the changes made.

Git has some naming-conventions, that tells you to write a commit

- short (<50 characters)

- written in present tense

- expressive

| |

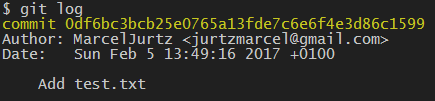

The output of this command looks like the following:

- SHA1-checksum

- Name of the author

- Email of the author

Configuring names and emails

This configuration is global for every repository (set it up once per device).

| |

You can set this for each project individually, just leave out the -global-flag.

HEAD

In the following, HEAD is often mentioned. HEAD is the most recent commit of the current branch.

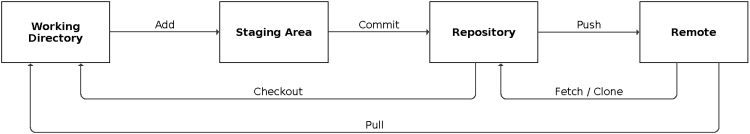

Using Remotes

A remote is a repository on a server / different pc, for example hosted on Github.

In the following, I use Github as remote server.

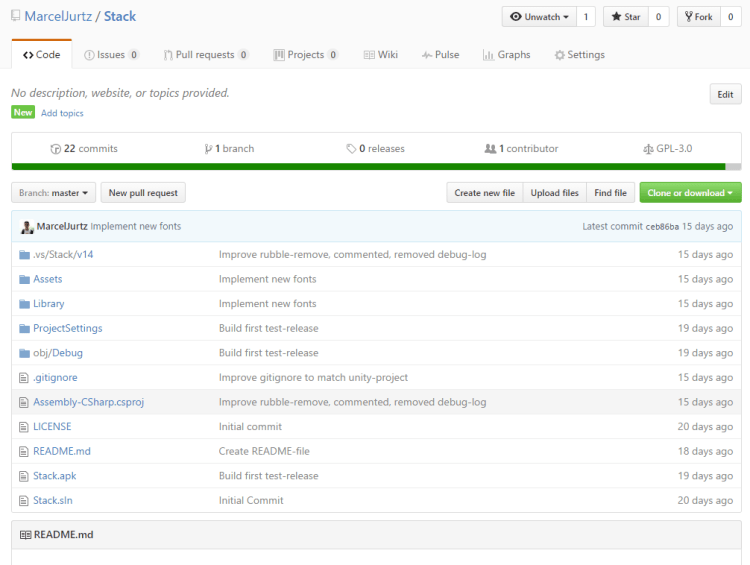

After creating an account on Github, available repositories are shown and new ones can be created.

When creating a new repository, you can select to add a README- and/or license- & .gitignore-file.

When creating a new repository (of course this can be done later as well), you are prompted to create a README-, license- and .gitignore-file:

- README is a file that represents general information about the project. When hosted on GitHub, this file can be imagined as landing page for visitors. README-files are usually written in markdown. Markdown is similar to HTML, but has lesser functionality and better readability (in my opinion).

- license: All repositories on Github (free accounts) are publicly available. With a license-file, the usage of the repository can be adjusted to different preferences. GitHub offers some pre-defined licenses, for example MIT and GPLv3, along with information on the differences.

- .gitignore: Gitignore-files list files and directories, that will be ignored by git. You can add files and folders, to, for example, prevent temp- or meta-files from being added to the repository.

The following screenshot shows an exemplary repository on Github.

The lading page offers some overview of a repository, for example the files and folders in the root-directory, amount of commits, branches, licensing-info and so on.

After a repository has been created, it can be added as a remote:

| |

You can set individual names for the remote, I use origin here.

To upload changes commited in the working directory, use the following:

| |

And this to download changes from a remote:

| |

Please know that if you have an existing project on your pc and want to add it to a remote, which already contains files, for example README, license, or .gitignore,

youll have to merge the repositories. If you don’t have any of these files locally, you’ll have no problems, since the files will be automatically implemented.

If you do, this will result into a merge-conflict. Continue reading, to find out more about merging.

Merging

For example, user A and user B are editing the same repository, both users can work with the above mentioned methods.

A problem comes up, when both users push the same file: merge conflicts.

Think of a file in the remote repository named test.txt, which has the following content:

Hello

Using pull, both users get this file to their working directories.

Now, both users edit the file to the following:

Version A:

Hello, I am A!

Version B:

Hello, I am B!

Both users now push their version to the remote. The user submitting first will have no problems doing so. In my example, this will be user B.

When user A pushes his updates, the push will result in an error like the following:

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in test.txt

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Git now modified the mentioned files, test.txt now has the following content:

<<<<<<< HEAD:test.txt

Hello, I am B!Hello, I am A!

>>>>>>> commit-text:test.txt

A now has to decide, which version is preferred and then commit the changes.

A updates the file to the following:

Hello, we are A and B!

After that, he creates a new commit to document the merge:

| |

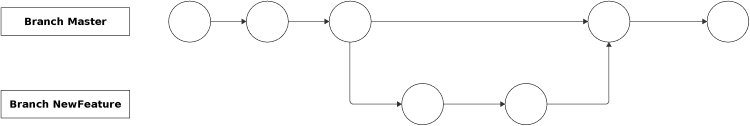

Branching

Git uses branches to support developing new features. This supports developing new functionality, without the need to edited the working current version of the project.

Use this to create a new branch:

| |

And this to view all existing branches:

| |

The current branch is marked by an asterisk. Usually, this is master in new projects. As you may notice, we used this branch earlier to push commits. Replace this to push to other branches.

Changing branches

| |

Creating a branch and switching to it:

| |

When a branch is changed, files in the working directory are automatically updated to match that branch. This way, you don’t have to use different folders for different branches and save space on your harddrive.

To merge two branches, switch to the branch you want to merge to (using git checkout) and merge them:

| |

To view differences in branches, you can use

| |

Branches, that are no longer needed, can be deleted:

| |

Tags

Tags can be added to commits, to highlight completed versions of a project. To select a commit, the first 10 characters of the checksum are needed (git log).

| |

Resetting changes

To reset contents of the working directory, you can use the following:

| |

This command obtains changes from HEAD and overwrites the content of the working directory to match HEAD. Changes that have been added to the staging area are not overwritten!

To reset contents of the directory, use this:

| |

As shown earlier, you need to add the first characters of the commits checksum to identify the commit. This command should only be used with caution, since it changes the commit-history.

Conventions & Good Practices

To keep repositories as clear as possible, you should follow some general rules in naming commits and branches.

Commits

Commits should be written under considering the following:

- Keep it short and simple

- Begin with a normalized set of verbs, written in present tense, for example: add, remove, update

Branches

It is useful to use a short and precise formulation here as well. Often, a verb as prefix is used to describe the purpose of the branch. For example: add/feature_a, remove/feature_b.

When contributing to public projects, you should also check the previous commits to adjust to the organization of the other authors.

Alternatives

If you don’t like using the terminal, there are some GUI-clients. For example: